By C.W.S.

I have long been fascinated not only with the psychology of serial murderers, but also the concept of the American teenager, and the psychological aspects of what that represents. Teen-hood is the original flesh of life, the vibrant, painful experience of facing a world with an evolving sense of right and wrong, of personhood, of a becoming that feels so immediately important that teenagers are consistently seen as moody, as mean, as dramatic. And of course this is true, but there is a good reason. Teenagers are leaving the realm of imagining, of childhood, and are forced then to position themselves as young adults, ridding themselves of anything fantastical quickly, reaching suddenly toward what humanity reaches for most desperately: sex (whether we want to admit it or not). And how soon adults forget what it was like, and how soon they will write off real issues as nothing more than teenaged hormones.

Teenagers are lonely, teenagers are misunderstood. It’s absolutely true that teenagers are raging with new hormones, and these hormones render their own selves unrecognizable. Remember? Suddenly, your friends are different, and you are different. Teenagers are romantic to a fault, throwing themselves around the world, at each other, trying to find something to grip onto as their lives roll forward toward an unknowable future. You see things differently, you feel things differently, and there is nothing that can be done, outside of finding people who understand. That is, if you’re lucky.

So, what happens when a teenager is faced with feelings that exceed the typical? The graphic novel, My Friend Dahmer (which later became a movie of the same name), written and illustrated by Derf Backderf, is a first-hand account of the author’s high school friendship (or something like that) with Jeffery Dahmer. Backderf seeks to demonstrate that Dahmer showed early sighs of neglect, alcoholism, and emotional turmoil that the adults in his life, especially those at his school, either didn’t notice or chose to ignore.

In My Friend Dahmer, Backderf is a typical teenager in the late 70s, his family life normal, his friend group tight knit and mischievous, admittedly using Dahmer’s strangeness for their own entertainment. Dahmer’s shtick, according to Backderf, is an imitation he did of his mother’s nervous breakdowns, in which she would shake and twitch and make strange noises until she exhausted herself. Dahmer was making humor out of a painful home life, where his mother was mentally ill with a severe untreated anxiety disorder or perhaps something more severe. His father and mother fought constantly, and when their marriage ultimately ended in an ugly divorce, they left Dahmer to live alone in the house, his mother choosing to take his brother with her, but not Jeff. All this happened before he graduated.

Dahmer walked the halls of the high school in an army fatigue jacket, drinking beer and liquor he smuggled inside the lining. He was smart, teachers recall, but his disinterest led to average grades. He had few friends, and most considered him weird. He could be the awkward star of a late 70s teen movie, drunk during lunch, too smart for school, lacking any motivation, going after girls aggressively with little luck. But, as we know, Dahmer was after something different.

Before Dahmer was a serial killer, he was a closeted gay teenager. But that isn't actually accurate. His sexuality manifested in another way: he was attracted to dead bodies, ones which happened to be male. We all know about the jogger that Dahmer first stalked, watching him and dreaming of rendering his body immobile and doing what he wanted with it. He waited one day with a bat, ready to knock the man unconscious. But on that particular day, the jogger never came by, and for whatever reason, Dahmer did not make a second attempt. But his desire to pursue necrophilia continued to grow, with seemingly no way to escape it.

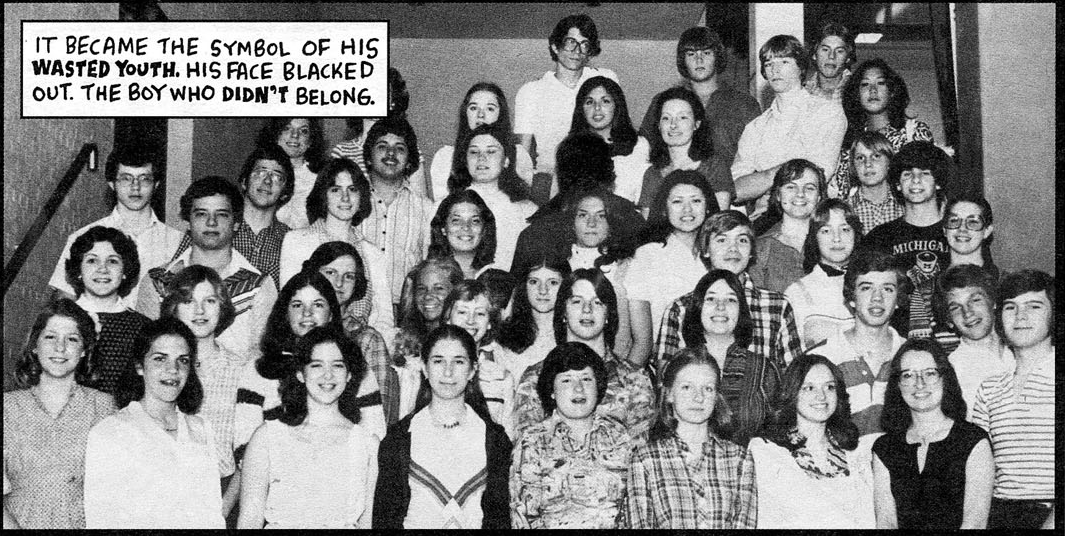

Through research as well as personal experience, Backderf also takes the liberty to imagine Dahmer’s private life throughout high school. Backderf contributes Dahmer’s alcoholism to an attempt to quell his brutal thoughts and desires, as well as a way to escape his own dysfunctional reality. Constantly wasted, Dahmer would hide liquor around the outside of the school, always smelling strongly of booze, arriving early and leaving in the dark, stalking around and drinking, believing it safer to do so near the school than at his own home. Backderf shows Dahmer out in his shack in the woods where he conducted strange experiments on animals, dissolving them in acid, bleaching their bones. It shows Dahmer walking alone, screaming at his own compulsive, ugly thoughts. The book shows Dahmer going to prom with a girl, and then walking out to sit alone at a McDonalds. The book shows Dahmer blacking out his own face in the high school yearbook.

Backderf tells us to pity, not empathize with, Dahmer. In the preface of the book, he states: “Once Dahmer kills, however—and I can’t stress this enough—my sympathy for him ends. He could have turned himself in after his first murder. He could have put a gun to his head.” He knows, and states as much, that Dahmer’s life was difficult, but not as traumatic as many other serial killer upbringings. Backderf knows that many of our lives have been difficult in similar ways, and yet we do not do what Dahmer ultimately did: murder, dismember, cannibalize, and rape the dead bodies of his at least 17 victims. The book comes to a close with Dahmer’s first murder, 18-year-old hitchhiker Steven Mark Hicks. This murder was committed just three weeks after graduation. Backderf is no bleeding heart, nor does he shy away from his own guilt around how he treated a teenaged Dahmer who was clearly suffering. But what he does do is ask the question again and again: Why did no adults step in to help? Why didn’t they smell the liquor on his breath, see the suffering in his stance, why didn’t they do something?

Backderf is under no illusion that Dahmer could have been “saved” from his own terrible life. He knows that regardless, Dahmer would have had to deal with his own psychological terror, probably forever. The difficulty is that Dahmer did not choose to have these thoughts and feelings, but he did choose to follow through on them. Backderf envisions him weighed down under a cocktail of pharmaceuticals, but knows that this would be preferable to the hell he imagined Dahmer lived in without psychiatric help, not to mention preferable for his victims and the world at large. To Backderf, it wasn’t as much about helping Dahmer as it was seeing the warning signs that a kid needed help, help which could have led to an awareness of his proclivities, help which could have saved many lives.

We need to value the feelings and problems of teenagers, instead of laughing them off, instead of chalking them up to hormones, to dramatics, to moodiness. I can think of so many teenagers growing up that needed support in ways that we did not receive: issues around mental health, substance abuse, family life, identity. Of course, these are topics much easier addressed than necrophilia, and yet… they are not addressed nearly enough.

While I read My Friend Dahmer, I was reminded of a guy I grew up with who exhibited early signs of sexual dysfunction, calling after the girls in vulgar ways, starting as young as 10 years old. He was clearly in need of special education, of some kind of adult intervention, of help instead of punishment, which he did not receive. Some of us other teenagers showed him care, understanding that something was wrong, despite his abhorrent behaviors, and sometimes I could tell he responded to this care with gratitude. But none of the adults, not his parents, not his teachers, offered him any real help. Just a couple months ago, he was arrested as part of a child pornography ring, ten years after graduation, shocking the town in which I grew up, but not completely. Many of us said, Well, if it was going to be someone… It wasn’t a surprise. But if we knew that this kid needed help, even then, even as self-absorbed teenagers, just like Backderf asks explicitly in My Friend Dahmer: “Where were the damn adults?”

Purchase Derf Backderf’s graphic novel My Friend Dahmer here.