By C.W.S.

In his first media interview in over a decade, 70s-era serial killer David Berkowitz, known as the Son of Sam, spoke from prison with CBS correspondent Maurice DuBois in a segment that aired earlier this month.

The aging Berkowitz first appears on camera passing by a window while walking to the prison chapel, where he has chosen to sit and talk with DuBois. Dubois watches him, guessing that he has just caught his first real glimpse of the infamous Son of Sam that terrified New York in the late 70s when he shot and killed six people and wounded seven others in murders that happened most frequently to young people parked on “lovers’ lanes.”

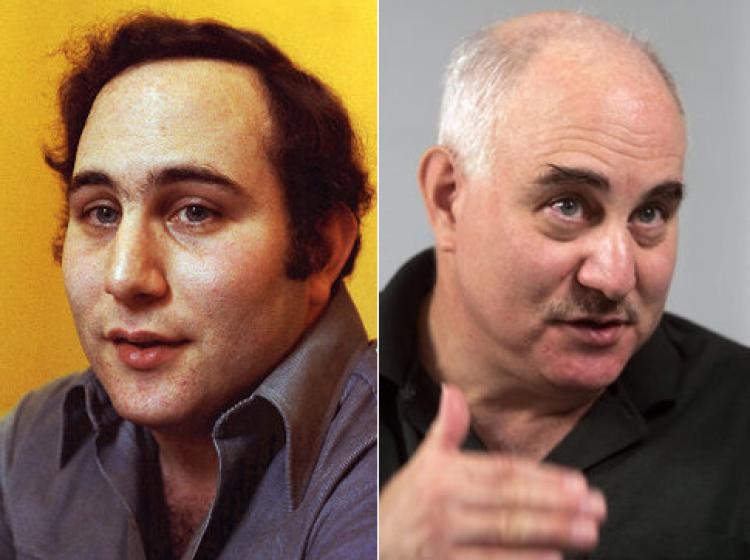

This Berkowitz is hardly a common picture of evil. Short and stalky in stature, his head is perfectly bald and wrinkles sit heavy on his forehead. His eyes are bright and clear, sympathetic, both child-like and ancient, ringed with a wetness. He speaks slowly and almost dismissively, with a hint of defensiveness. He is sorry—that is something that he does not shy away from. But when it comes to taking responsibility, sole responsibility, he does shy away. How could this be?

In the mid 1990s, 13 years after his arrest, Berkowitz changed his official confession. He told investigators that he had been part of a Satanic cult, and that his murders were done as ritual killings for the group. Despite the fact that detectives did not find his claims to be credible, the case was reopened in 1996, and then suspended indefinitely when no new evidence was found. Authorities at this time believe that Berkowitz acted alone.

Berkowitz in the new CBS interview

But that’s not exactly what Berkowitz was referencing in this new interview. He is claiming, yet again, that the murders were caused by a demon, or demons, working through him.

Growing up, Berkowitz had loving parents where he lived in the Bronx. Psychiatrists claim that the discovery of his adoption, and the subsequent lie that his birth mother was deceased, acted as a primary crisis in his life. In the interview, he tells DuBois that as a result of this confusion, he “struggled with self-destructive behavior,” but does not blame his adoptive parents for the lie—he shows understanding toward them and praises them as parents. Berkowitz was known by neighbors as a difficult kid, a bully, spoiled. Berkowitz recalls his struggles as a young person with depression and an obsession with death, stating, “I thought I deserved to die,” but doesn't explain why.

His adoptive mother died when he was 14, a pain that Berkowitz claims to still carry with him. He speaks of his shame and guilt around the event but also doesn’t explain the reason for those feelings. He connected with his birth mother at the age of 18 after a military tour in Korea and an honorable discharge, but later ended contact. The apparent details of his “illegitimate birth” were very disturbing to him.

When he returned from Korea, Berkowitz claims he had normal hopes and dreams of a family, a home, a career. But that all fell to the wayside several years later, as his crimes and obsessions with young women intensified, leading to his first murder in 1976 of Donna Lauria, and the attempted murder of her friend, Jody Valenti. Berkowitz would injure or kill 11 more people in the New York area before his arrest in 1977. The media would notice a commonality among his female victims: they all seemed to have brown hair.

Berkowitz is most famous for the strange letters he sent to Jimmy Breslin of the Daily News. The first was received shortly after the killing of Donna Lauria:

Hello from the gutters of N.Y.C. which are filled with dog manure, vomit, stale wine, urine and blood. Hello from the sewers of N.Y.C. which swallow up these delicacies when they are washed away by the sweeper trucks. Hello from the cracks in the sidewalks of N.Y.C. and from the ants that dwell in these cracks and feed in the dried blood of the dead that has settled into the cracks. J.B., I'm just dropping you a line to let you know that I appreciate your interest in those recent and horrendous .44 killings. I also want to tell you that I read your column daily and I find it quite informative. Tell me Jim, what will you have for July twenty-ninth? You can forget about me if you like because I don't care for publicity. However you must not forget Donna Lauria and you cannot let the people forget her either. She was a very, very sweet girl but Sam's a thirsty lad and he won't let me stop killing until he gets his fill of blood. Mr. Breslin, sir, don't think that because you haven't heard from me for a while that I went to sleep. No, rather, I am still here. Like a spirit roaming the night. Thirsty, hungry, seldom stopping to rest; anxious to please Sam. I love my work. Now, the void has been filled. Perhaps we shall meet face to face someday or perhaps I will be blown away by cops with smoking .38's. Whatever, if I shall be fortunate enough to meet you I will tell you all about Sam if you like and I will introduce you to him. His name is "Sam the terrible." Not knowing what the future holds I shall say farewell and I will see you at the next job. Or should I say you will see my handiwork at the next job? Remember Ms. Lauria. Thank you. In their blood and from the gutter "Sam's creation" .44 Here are some names to help you along. Forward them to the inspector for use by N.C.I.C: [sic] "The Duke of Death" "The Wicked King Wicker" "The Twenty Two Disciples of Hell" "John 'Wheaties' – Rapist and Suffocator of Young Girls. PS: Please inform all the detectives working the slaying to remain. P.S: [sic] JB, Please inform all the detectives working the case that I wish them the best of luck. "Keep 'em digging, drive on, think positive, get off your butts, knock on coffins, etc." Upon my capture I promise to buy all the guys working the case a new pair of shoes if I can get up the money. Son of Sam

Over the following months while the murders continued and the public grew desperate, Jimmy Breslin would interact with Berkowitz through the Daily News, sometimes taunting him in an attempt to gain more correspondence for police investigation, as well as more readership. At this point, the hysteria over the Son of Sam was reaching a fever pitch, with young women staying indoors and dying their hair blonde, with vigilantes roaming the streets, with newspapers dedicating eight pages a day to the story.

Donna Lauria and Jody Valenti

Berkowitz was apprehended in a parking lot after a witness spotted him leaving the scene of the murders of Stacy Moskowitz and Bobby Violante in Brooklyn, with a parking ticket on his car. The police were able to identify Berkowitz through the ticket and tracked him down soon after. In his confession, Berkowitz would famously claim that he was commanded to kill by his neighbor “Sam,” making more clear the references to "Sam" in his letters, as well as the nickname he had given himself. Berkowitz said that he communicated with him through Sam's dog, Harvey, the black lab that Berkowitz shot and killed before his arrest. Despite these outrageous claims, he was deemed fit to stand trial. He was sentenced to 25 years to life.

When asked about why he committed these crimes, Berkowitz told DuBois: “It was just a break from reality. I thought I was doing something to appease the devil, and I’m sorry for it, but I really don’t want to talk—”

“Appease the devil?” DuBois interrupts.

“At this time I was serving him. I felt that he had taken over my mind and body, and I just surrendered to those very dark forces. I regret that with all my heart, but you know, that was like 40 years ago.”

Berkowitz seemed most interested in talking about his conversion to Christianity, in which he became a born-again evangelical, going on to become a prison minister. But DuBois seemed determined to get Berkowitz to talk more about the killings and why they happened, of which he was very reluctant. “Whatever,” he says at one point when DuBois speaks about the names the media created for him, “I don’t want to discuss that.”

He continued to be prickled by the questions, “Again, it’s just the way things turned out. It’s regrettable, that’s it.”

He made multiple references to his own pain, more so than to the pain of his victims or their families. Each time a reference to their pain was brought up, Berkowitz sympathized quickly, but then turned the conversation back to himself, almost as if the crimes were not his at all. When DuBois points out the irony that Berkowitz, who experienced the painful death of his mother at a young age, caused so much of the same kind of pain to others, he responded:

“It’s very painful. I carry around a pain too. Not the same kind, but I’m aware of what happened. I draw comfort, if you can call it that, by reading about it in the scriptures, about some of the well-known Bible characters that did very bad things and how God forgave them, and God was able to use them in very special ways, very unique ways, and they became what we call ‘champions of the faith.’ The Lord did a lot of work in my life, you know. That’s why I try so hard to give a cautionary tale to young people about not getting involved in Satanism or the occult or those kinds of things—because I feel they too could maybe take a bad path.”

He seemingly shirked responsibility for his crimes again and again, not wanting to take 100% of the responsibility. “Lets put it this way. There were demons, but I take responsibility.” He references the demons multiple times in the interview in ways that lend them at least some of the responsibility.

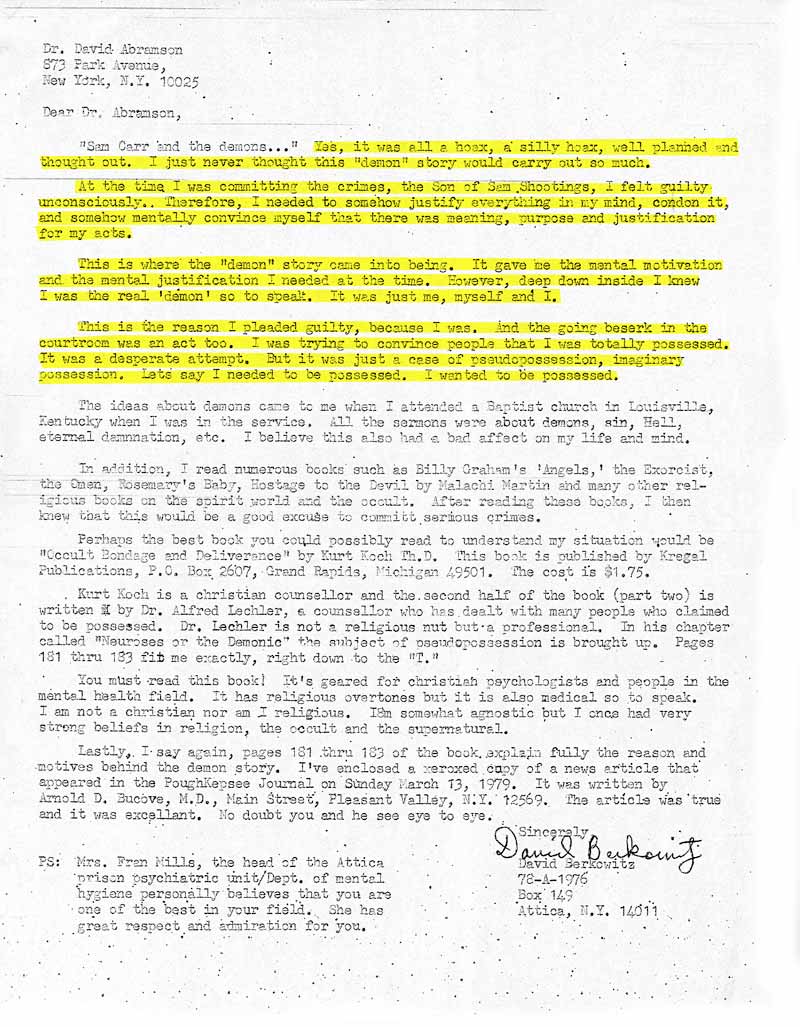

Now, here is the problem with this version of the truth, beyond the obvious. Berkowitz admitted in 1979 that his claims of demonic possession were nothing more than a convenient hoax he created. Through several interviews with his court-appointed psychiatrist David Abrahamsen, he revealed that the demons were an easy excuse he knew he could use to commit violent crime without responsibility. He felt the world had rejected him, hurt him, and he wanted to get revenge, especially against women in general, who he believed did not pay him the attention he wanted.

So these bogus new claims of demonic possession are simply another attempt at excusing what was a crime of violent misogyny, of a hatred of women probably stemming from anger at both his birth mother, and women in general. Berkowitz famously taunted the courtroom and the family of Stacy Moskowitz during his trial, saying over and over in a sing-song tone, "Stacy was a whore." The attempt to make this into a more sensational story by Berkowitz shows a dangerous personality disorder, one that focuses on Berkowitz’s own pain as somehow both more important than his victims and their families, as well as a sense of grandiosity around his conversion to Christianity and his past crimes. Throughout the whole conversation with DuBois, Berkowitz is focused on one thing: himself. And though his appearance is old and kindly, his voice soft and calm, there is still a clear disconnection from the reality that most of share, where demons do not cause murder, but volatile, unchecked personalities do.

Berkowitz claims that it was Psalm 34:6 that saved him and caused his conversion: This poor man cried, and the Lord heard him, and saved him out of all his troubles. It seems like that was exactly what Berkowitz had been looking for: a chance to to be absolved of his crimes without the true personal responsibility it takes to deserve such forgiveness.