By C.W.S.

Warning: This content contains descriptions of sexual abuse and violence toward children

With the long-awaited discovery of Jacob Wetterling’s remains in rural Minnesota, I can’t help but think of the other kids who disappeared or made headlines in the 1970s and 80s. Vanished or allegedly abused while doing what kids do—delivering the paper, riding a bike, playing video games at the mall, walking home from a bus stop, spending the day at a preschool. Headlines about these children changed the United States in a myriad of ways, both legally and in a very real sense, emotionally. These were the kids on the milk carton, the kids on the news, the faces that represented the growing fear of the randomness of this new and particular cruelty, a fear that would grow out of control, not necessary because the threat was statistically probable, but because fear has a way of multiplying inside of us, of taking us over completely.

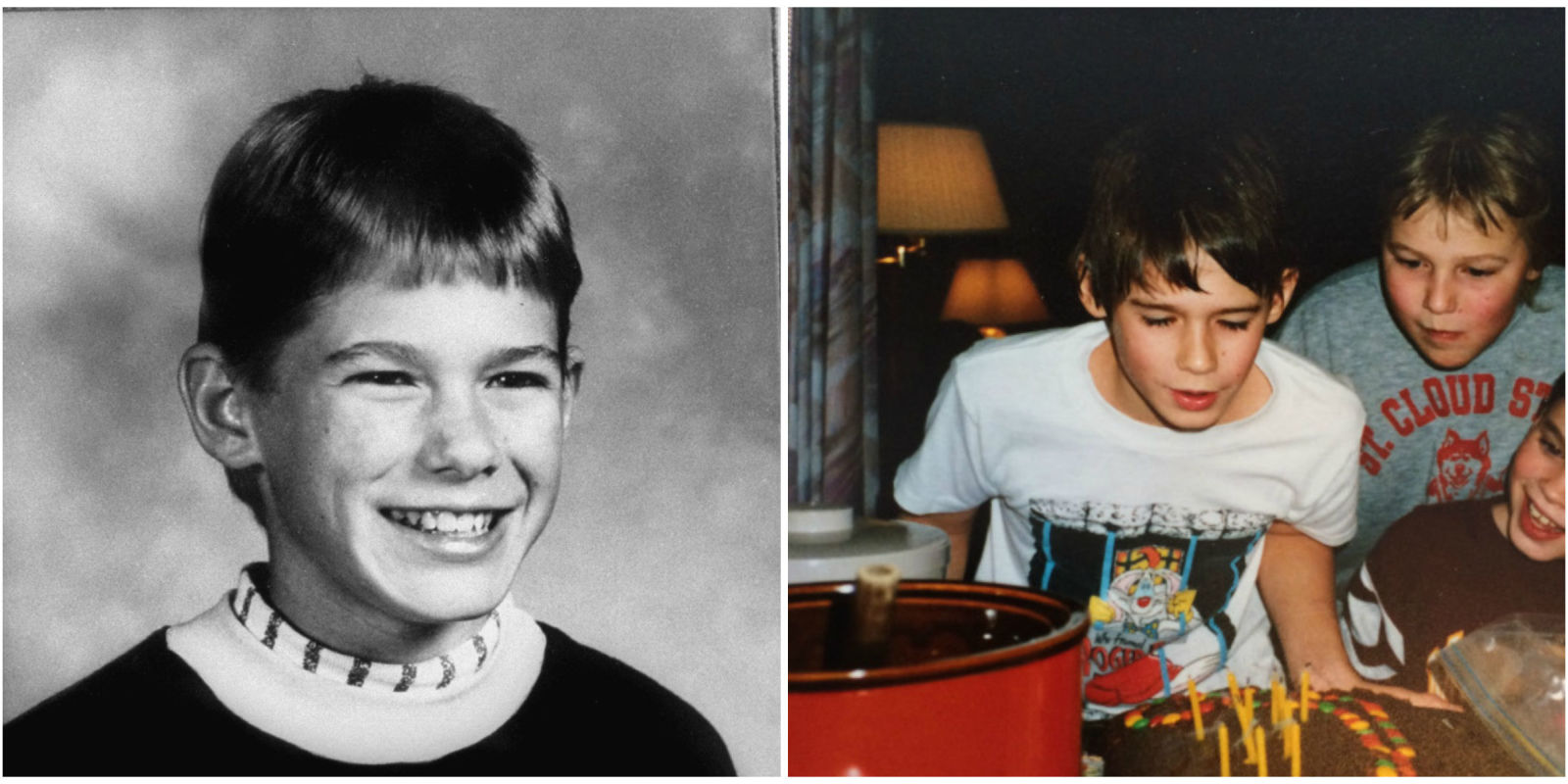

Jacob Wetterling

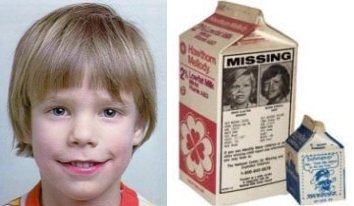

You wake up in the morning, you’re a child or you’re a parent, and you sit at the breakfast table, reading the cereal box, reading the milk carton. And you see a face; it’s one of the first things you see. Our mornings set the course of our days, and of course, that’s why missing children were put onto milk cartons. We see them in the morning, we think of them all day. And the next morning, their faces are there again. Before these boys, most of this country was not aware of child predators, many didn’t even know the word “pedophile.” But the fear of these child predators would grow and grow, eventually breaking into a nation-wide hysteria. Jacob’s disappearance fell neatly into this timeline.

I’ll be honest. I was one-year-old when Jacob disappeared. I was not around for the days when there wasn’t a grave fear of strangers, of sexual predators, of kidnappers. I grew up in the 90s, when this fear was certainly there, when “stranger danger” was a term you heard on TV commercials and after-school specials at an almost constant rate. But it was a fear not yet completely cemented. I still did things that most kids now would never be allowed to do—I rode my bike to the store, took the bus to the city, walked the streets at night. I cherish these memories: the sense of an expansive childhood freedom that seems to be disappearing completely from the experiences of our youth. Would I condone all the things I got away with? Not totally. The world is scary, of course it is, and we must protect our children at all costs. But don't we want to protect them in more ways than just physically? Mustn't we also care for their emotional health, so that they can grow up to be well-adjusted, so they can relate to the world realistically, rather than with unnecessary anxiety?

Though we kids were freer back in the 90s, there was still a very palpable nervousness surrounding me and all my friends. We had all the stranger danger talks. We all had a secret password with our parents, so that if a strange person tried to pick us up from school, we would know if it was okay to go with them or not. That stranger never came for me.

But that stranger did come for others. That stranger with a plan, a stranger like Danny Heinrich, the man who just confessed last September to sexually assaulting and murdering 11-year-old Jacob Wetterling on October 22, 1989. He watched Jacob, his younger brother Trevor, and his best friend Aaron bike by in the dark on their way to rent a movie from a local store. Heinrich waited for the boys to come back on the same road, and then approached them with an unloaded revolver, telling them to lie face-down in the ditch. He asked the boys their ages. He told Trevor and Aaron to run into the woods and not look back. It was the last time anyone ever saw Jacob Wetterling alive.

Etan Patz

Etan Patz was one of the very first missing children to be printed on a milk carton. He disappeared on May 25, 1979, on his way to catch the school bus in Manhattan. On the fourth anniversary of his disappearance, Ronald Reagan made May 25 “National Missing Children’s Day.” It wasn’t until 2012 that police were able to charge Pedro Hernandez with murdering Etan after he confessed.

Adam Walsh

And then Adam Walsh’s murder in 1981. Adam was the son of John Walsh, who would go on to become the host of America’s Most Wanted, my very favorite show that I watched every Friday as a kid. I knew that John Walsh’s son had been murdered, taken from a Sears in Florida. I knew even about the acute brutality of the murder, only his severed head found. Every Friday John Walsh would point at me through the screen. Every week he would talk about “the bad guys,” and every week I wondered when it would be my turn to meet a man like that.

The next boy to gain serious national attention was Johnny Gosch. Johnny left his Iowa home just before the sun rose on September 5th, 1982. He picked up the bundle of papers he was to deliver that day, and was never seen again. Many suspect that he was trafficked into a child sex ring, abducted by another trafficked boy, Paul Bonacci, who admitted many years later to helping in the abduction. Johnny is still missing to this day.

Johnny Gosch

Soon after came the national hysteria known as the “Satanic Panic” that piggybacked on the new, widespread fear of child sexual abuse. Perhaps because the thought of abusing a child in such a way is so horrific as to be completely unimaginable to most people in the United States, it needed a clear label to define its seemingly unexplainable evil. Then came reports of Satantic ritual abuse out of one bogus memoir: Michelle Remembers.

Written with her psychiatrist, whom she would later go on to marry, Michelle Remembers was published in 1980 and alleged that Michelle Smith had suffered severe physical and sexual abuse as part of several Satanic rituals carried out by her parents and their Satanic cult. The book coined the term Satanic Ritual Abuse, and also attempted to develop the concept of repressed memory, and come 1983, a full-blown hysteria swept the US, illustrated best by McMartin preschool trial.

It was a woman by the name of Judy Johnson who initially believed her son was being abused at the Manhattan Beach, CA daycare center. Because her son was having painful bowel movements, Johnson reported to police that a teacher at the school had sodomized her son. Then, police did a strange thing. They canvased the school and told parents to ask their children if they had been abused at the daycare. What followed was an onslaught of wild accusations from parents due to the things their children had said. These events included seeing witches fly, traveling in a hot air balloon, having orgies at car washes and in airports, and even children being flushed down the toilet to secret rooms where they were abused. All of this was said to have happened in the time the children were under care at the daycare center. And it went to trial with testimony such as this.

By 1984, Children’s Institute International had interviewed hundreds of children, and claimed to have statements of ritual abuse from 360 children. The whole trial lasted from March 1984 until 1990. All of the accused were acquitted, and it was discovered that Judy Johnson suffered from acute paranoid schizophrenia, information that was not given to the jury. She died in 1986 in the middle of the trial due to severe alcoholism.

Psychologists believe that both Michelle Remembers and the accusations made during the McMartin Preschool trial were due to a psychological phenomenon called false memory syndrome, or the idea that memories can be altered and even inserted through outside suggestion and influence. Parents and other trusted adults can create horrifying false memories for children. This is the power of our projected fears.

Bogeyman: a common allusion to a mythical creature in many cultures used by adults to frighten children into good behavior.

With 1989 Jacob’s disappearance, Jacob’s mother Patty dedicated herself to creating a better world for children. There came an onslaught of new legislation aimed at stopping child sexual abuse. Passed in 1993 and called the “Jacob Wetterling Crimes Against Children and Sexually Violent Offender Registration Act,” these laws are something we have all become very familiar with, but we know it as the Sex Offender Registry.

But here’s the thing. Only about 115 children are taken by strangers in the United States each year. That’s a 0.000002% chance that a child will be abducted by a stranger. Almost all cases of child sexual abuse are perpetrated by family members or someone the child knows very well. But, as Patty openly speaks about, sex offender registries have not led to a decrease in sex crimes, and teenagers are appearing on the registry for things like sexting another teenager. For things like public urination.

Almost all sex crimes against children occur not from strangers, but from family members and people close to them, and yet, do we teach our children to fear their own family, to fear those closest to them? Statistically, these are the bogeymen, and yet we continue to prefer a belief in a random stranger, because, in a sense, it is less painful to believe.

I remember the fear around poisoned Halloween candy, a fear that was reported on the local news year after year, with examples of properly sealed candy, and examples of candy that could have been tampered with by a local villain, so impossibly evil as to poison kids at random for his own entertainment. This has never happened and yet every year, to this day, this viral urban legend persists. And because of this type of fear, Trick or Treating, one of the best experiences of my childhood, seems to be disappearing completely.

Danny Heinrich

When I was in elementary school, two girls the grade above me made the local news when they reported a strange man had chased them at the middle school park. The two girls gave descriptions of this man, old and haggard, with a scar down this face. There were police sketches shown on the news, and I was no longer allowed to walk anywhere alone. An almost-instantaneous curfew materialized, not due to police demand, but due to parental reaction.

Is there anything wrong with that reaction? Of course not. But, if you haven’t already guessed, those two girls made up the whole thing so that they wouldn’t get in trouble for coming home late. It was my town’s own miniature hysteria in the mid-90s, and everyone bought it hook, line, and sinker. This is not a bad thing. We should always take accusations from anyone seriously, especially from the children we are supposed to protect. Because “the bad guys” do exist, and too often police and families ignore allegations of abuse. The problem is that “the bad guys” are almost never the people we expect, not devil worshippers that have taken over a preschool to use our children in evil rituals, not maniacs killing kids with poison candy, not these random monsters stalking for child prey,

But Danny Heinrich is real. He is a real man who harmed real children at random. So is the man who took Etan, the man who took Adam. Most likely, the man who took Johnny. This reality, though a harrowing one for a nation to hold, has been overblown into something not only illogical, but potentially harmful. Illustrated perfectly by the McMartin Preschool Trial, our children are incredibly suggestible, absorbing everything around them, most especially, adult fear.

And what are the long-term consequences of something like the McMartin preschool trial on the psychology of our youth? Can our fears lead us to do the exact thing we hope to stop: the harming of children, not a physical or sexual harm, but an emotional, spiritual harm?

When we let our children be defined by our adult fears, what freedoms do they lose, what chance at believing in a better world? What unnecessary anxiety will they carry? Maybe the bogeyman is just fear itself, fear grown so out of proportion that it manifests itself anyway—in false memories, in bad dreams, in the restrictions we place on our children and on ourselves. Maybe the bogeyman got us in the end anyway, because maybe he was in us all along: our own fear made manifest in the world around us.

Patty Wetterling

Even Patty Wetterling, who experienced the very tragedy that American families dread the most, had this to say: “It’s all the fear. I think fear is really hard for me in this topic because you’re more likely to get struck by lightning than to be kidnapped, you know? But the fear of sexual abuse, especially with parents, is huge. And they think that making their kids scared is going to keep them safer which is absolutely not true. It’s probably the opposite.”

For further information about the Jacob Wetterling case, as well as more information around many of topics written about here, may I recommend the incredible podcast that inspired this piece: In the Dark by APM Reports.