By C.W.S.

As people interested in true crime, we often get flack for our interest in such a gruesome topic. But imagine living in England in the 1600s, where criminals were hanged publicly in front of enormous crowds of tens of thousands in the largest social gatherings of the time. Parents would bring their children and a picnic out to the gallows to watch criminals die by hanging, and sweethearts would sit on the shoulders of their boyfriends, just like a rock concert. People would drink too much and end up fighting, rolling around in the mud.

In 17th and 18th century England, there were a whole lot of offenses that could get you hanged. In fact, there were about 200, including crimes that can still carry the death penalty today in some US states, such as murder, and others that we would find ridiculous today, like witchcraft and heresy. Treason, robbery, and counterfeiting money were some of the more serious offenses, but stealing food and picking pockets could also carry death penalty sentences. Toward the end of this century, though, poor folks were starting to notice that poverty had become a death sentence, angry that they could not afford food and then could be hanged for doing what was necessary to survive.

Nonetheless, the crowds would flock to these public executions, and the mood would usually be jovial. With people rushing to get a good spot close to the gallows, these public spectacles were known irreverently as the “hanging fair”, “stretching”, or “collar day.” The events held a carnival-like atmosphere.

Vendors would show up early and set up their food and wares, much like a modern outdoor festival. They would make very good money at the event, selling food, drinks, and souvenirs related to the hanging. They sometimes went as far as to sell pornographic papers as well.

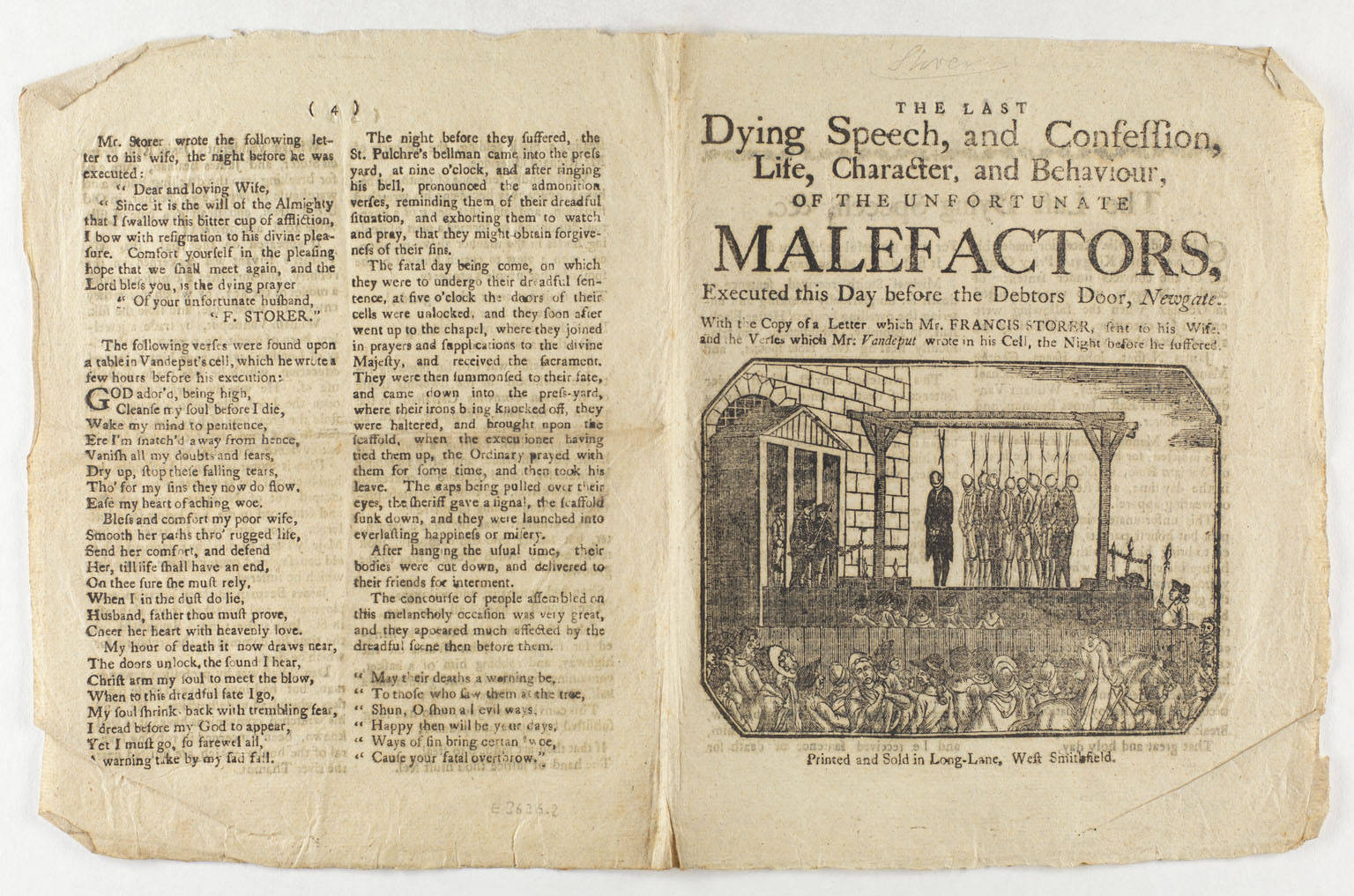

Pamphlets would be distributed at a cost to the crowds which claimed to have printed inside them the dying speeches of those who were being hanged. Known then as the “Last Dying Speech,” the quotes were usually fake, but they sold well nonetheless. These publications, known as broadsides or broadsheets, often had the same woodcut print image of a hanging that was reused at each event, and also gave apparent information about the condemned individual, and sometimes even poems or songs said to have been written by the criminal and found in their cell. Or sometimes it was something else very personal, like a letter written from the condemned person to a family member. Much of what was written was sensationalized, and often entirely fictional.

One such broadside from 1724 read:

This John Sheppard, a youth both in age and person, though an old man in sin…received an education sufficient to qualify him for the trade his master designed him, viz., a carpenter…But alas, unhappy youth! Before he had completed six years of his apprenticeship he commenced a fatal acquaintance with one Elizabeth Lyon, otherwise known as Edgworth Bess [a prostitute]…Now was laid the foundation of his ruin!

A typical broadside

Stands were often set up to hold more people and make sure they could see the “stage.” These stands were much like the stands of a high school football field, or those that fold out in a school gym. Sometimes homes near the execution sites would rent out their balconies. Seats in the stands and the balconies were very expensive, and the prices were raised based on the infamy of the criminal and of the crime. Sometimes these stands would collapse from the weight causing injuries and deaths, but it never deterred the crowds.

Those who were to be hanged had their hands tied in front of them at the local jail (so that they would be able to pray), and then they were driven in horse drawn carts through town toward the gallows, sitting on the coffins they would soon be buried in. Crowds would line the street to watch the procession. The condemned were allowed a stop at the local church, as well local pubs where the criminals were given drinks before taking their place at the gallows.

Sometimes the crowds would jeer and yell at the hangman, and be empathetic toward those who were about to be hanged, especially for crimes considered too minor for a death sentence. If a criminal was well-known, folks could be seen throwing flowers onto the stage. Other times though, crowds would throw rocks and rotten vegetables. They favored toward those who took their deaths with dignity, and seemed to despise those who showed fear or weakness, those who begged for mercy.

Folks who were about to be hanged were allowed to give a final address to the crowd. This act was supposed to afford the dying a last plea for forgiveness, but often that is not what happened. Sometimes angry at the rampant, institutional abuse of the time, the condemned person would use the opportunity to publicly shame the hangmen, clergymen, and the reigning monarchy. This often whipped the crowds up into riots, with authorities losing control. Other times, the victim did ask for forgiveness, giving long religious monologues (sometimes trying to buy time and pardons). Sometimes the person about to hang had gotten drunk on the way to gallows and addressed the crowds in swaying nonsense.

When it was time for the hanging to take place, it wasn’t a quick process. Since it was a short fall, their necks would often not break, and they would have to strangle to death, which took several minutes. Sometimes the families of the dying would be asked to pull down on the legs of their loved one to help speed the process along.

After they were dead, the crowds would rush the stage to try to get a souvenir from the body. Hangmen were known to flog the body in order to cut off pieces of clothing to hand out. The rope could also be cut up and sold, the cost based on the crime and fame of the hanged. These souvenirs would sometimes be found hanging above the fireplaces of those who were able to grab them.

So, sound like a good time?

Well, I'm very glad we no longer pack picnics to go watch people strangle to death for our own amusement. Nonetheless, there certainly is no harm in striving to be more moralistic when looking toward true crime as a form of entertainment. It’s important. Obviously.