By C.W.S.

The Christmas season we know now is an almost manically happy one. The cheerful shine of tinsel and the twinkle of fake snow, gifts wrapped tightly in bright colors and patterns, cookies and cider, Santa smiling warmly from his throne at the mall, adults in onesie pajamas, Elf on a Shelf. The most common story we hear in December is of a reindeer overcoming adversity to lead Santa’s sleigh, delivering new toys to all the good children. We watch Frosty the Snowman or A Charlie Brown Christmas, laugh and quote along to Elf or A Christmas Story, listen to the smoothest crooners sing the same mild songs we know so deeply in our bones.

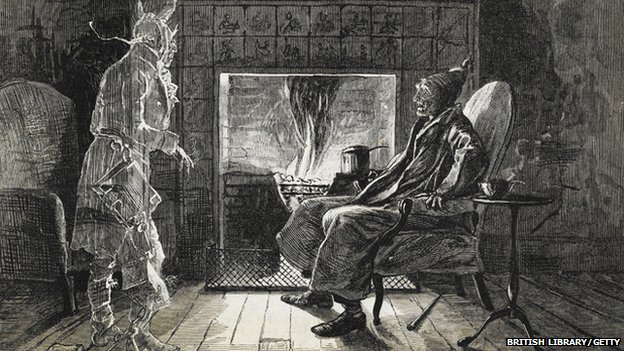

One story that we hear every year (often in its more current Muppet form) stands slightly apart: Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. There is an undeniable darkness to this tale that features not one, not two, but three ghosts that lead the rich sociopath Ebenezer Scrooge to have a more generous change of heart.

There was a time where stories like A Christmas Carol dominated the Christmas season. In fact, prior to 1915, ghost stories, and even stories of true crime, were a Christmas tradition. “Whenever five or six English-speaking people meet round a fire on Christmas Eve, they start telling each other ghost stories,” Jerome K. Jerome wrote Told After Supper, published in 1891. “Nothing satisfies us on Christmas Eve but to hear each other tell authentic anecdotes about spectres. It is a genial, festive season, and we love to muse upon graves, and dead bodies, and murders, and blood.”

Winter is a time of literal darkness and cold, and similar to fall harvest time when the dark begins loom, many communities throughout history have been prone to matching this loss of daylight with darker tales of woe. Combine that with the booze that flowed much more freely during holiday time and (just like my own family Christmas), tales of true crime and the paranormal also seemed to flow freely.

The wild hunt: Asgårdsreien (1872) by Peter Nicolai Arbo

Our Halloween and harvest time traditions have their origins in the Pagan holiday Samhain, and similarly, the darker aspects of Christmas have their origins in pagan tradition. “Christmas as celebrated in Europe and the U.S. was originally connected to the ‘pagan’ Winter Solstice celebration and the festival known as Yule. The darkest day of the year was seen by many as a time when the dead would have particularly good access to the living,” noted Justin Daniels, a religious studies professor.

Before the birth of Christ and the creation of Christmas, this season was known by the pagans as Yule and had some pretty ghostly lore. A common folk myth, The Wild Hunt, involved a group supernatural of hunters passing “in wild pursuit.” They were considered to be ghosts, elves, or fairies. If one were to see the huntsman passing, it was thought that they might be abducted and taken to an underworld or fairy kingdom. It was also considered to be a bad omen—one that might predict a coming war or plague.

Just like most awesome things that have been lost, it was the puritans who were to blame for the fading out of the more decadent and darker parts of the Christmas season. Super-puritan Oliver Cromwell, known as the Lord and Protector of England, Scotland, and Ireland, came ready to destroy all fun in the mid 1600s. He was “on a mission to cleanse the nation of its most decadent excesses. On the top of the list was Christmas and all its festive trappings,” Clemency Burton-Hill wrote for The Guardian. Most famously, Cromwell banned the singing of Christmas Carols (talk about a war on Christmas); he believed all these things to have pagan roots, which meant they were of the devil. This feeling spread to the New World, where protestants, especially the puritans, banned Christmas celebrations as well, and then, just to show the Catholics, worked all day long to prove their point. The industrial revolution also saw folks working longer hours and on holidays, and Christmas seemed to all but die out.

Oliver "No Fun" Cromwell

Come the 1800s, Britain and the US saw a resurgence of Christmas. Charles Dicken’s A Christmas Carol which was published in 1863, came around the same time as the invention of the Christmas card, and the subsequent commercialization of the holiday season in Great Britain in which gift giving became the main tradition. In classic English style, ghost stories caught on again as a result of Dicken’s work, and more and more authors began publishing them around Christmas time, and more and more folks began sharing their own around fires or dinner tables.

American author Washington Irving recounts stumbling onto a group telling Christmas ghost stories in the 1800s:

When I returned to the drawing-room, I found the company seated around the fire, listening to the parson, who was deeply ensconced in a high-backed oaken chair, the work of some cunning artificer of yore, which had been brought from the library for his particular accommodation. From this venerable piece of furniture, with which his shadowy figure and dark weazen face so admirably accorded, he was dealing forth strange accounts of popular superstitions and legends of the surrounding country, with which he had become acquainted in the course of his antiquarian researches.

As late as 1915, Christmas annuals were full of ghosts stories—in fact, it was their main draw. Lacking television, families would read these stories aloud and tell their own. But, the commercialization, as well as the invention of radio and TV, far outweighed the social aspect of Christmas time, and with it went the ghost stories. However, we can see evidence of the tradition in the lyrics of one of the most popular Christmas songs of all time, It’s the Most Wonderful Time of the Year:

There'll be scary ghost stories

And tales of the glories of the

Christmases long, long ago

It’s up to us to revive this tradition, to find the creepy glory of these Christmases of “long, long ago.” Us, the ones who miss terribly the plastic skeletons and Styrofoam graves of the autumnal grocery store aisle, who wince at assault of red and green that replaces it too soon. So this Christmas, maybe after a few drinks, offer up your best ghost stories. Who knows, maybe you’ll be surprised by who joins in.